It’s impossible to overstate the pain, frustration and despair that hundreds of patients faced before finding their way to CIM’s Amos Food, Body and Mind Center at Johns Hopkins, says psychiatrist Glenn Treisman, center co-founder.

“These were patients with significant gastrointestinal problems, who also were dealing with a host of other issues like migraines, chronic fatigue, depression and even hypermobile joints,” says Treisman. “Most had been very sick for years and had bounced from doctor to doctor, who couldn’t find anything wrong and told them their problems were ‘all in their head.’”

Fortunately, these patients finally found answers, and healing, when they made their way to the Amos Center, which was established in 2014 thanks to a generous gift from Courtney and Paul S. Amos. The center, which was co-created and co-led by Treisman and gastroenterologist Pankaj “Jay” Pasricha is considered to be the first clinic in the world that brought together gastrointestinal and psychiatric experts to treat patients in both physical and psychological distress.

The Amos Center truly shifted the paradigm by taking a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment. Where before patients with these complex symptoms would have endured an endless stream of appointments with different specialists — cardiologists, rheumatologists, gastroenterologists, nutritionists, pain medicine doctors, psychiatrists — the experience was dramatically different at the Amos Center. There, patients would meet together with a team of Johns Hopkins experts from varied clinical areas.

“We would all sit in the room together, sometimes even arguing about what we thought the problem might be, right in front of the patient. Our disagreements were no secret,” Treisman says. “Ultimately, over the course of an hour, we would come to consensus on the best path forward — and the patient would know why. Some would break down weeping, saying, ‘This is the first time anyone has ever listened to me.’”

“Some patients would break down weeping, saying, ‘This is the first time anyone has ever listened to me.’” – Glenn Treisman

Ultimately, as a result of this unconventional approach, Pasricha and Treisman would identify an entirely new syndrome, which defined about 75% of the 600 or so patients they saw at the Amos Center. Known as JAG-A, it is thought to be rooted in an underlying autoimmune disorder and involves a combination of four conditions:

By describing the JAG-A syndrome and the criteria that define it, Pasricha and Treisman have opened new pathways for treatment — at the Amos Center and among specialists around the country, who previously had been mystified by the unusual constellation of symptoms.

Through papers and presentations on JAG-A, they’ve shed light on new culprits in some people with disabling GI disorders: autoimmune disorders and/or dysautonomia (problems affecting the autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary bodily functions like heart rate, digestion and blood pressure).

“We now have objective tests that we can perform, which we didn’t have 20 years ago, that can help make a JAG-A diagnosis,” Treisman says. “These tests include whole gut transit imaging, where we can trace a piece of food that is eaten, such as a sandwich, and identify where there are delays in digestive function. In patients presenting with chronic pain, a skin biopsy can be used to identify small fiber neuropathy, “a sign that the autoimmune system is attacking the nerves,” he says. Patients also undergo testing for abnormal immune function.

As a psychiatrist, Treisman has been able to bring a vital perspective to diagnosing and helping to treat patients with JAG-A and related disorders, who often have associated problems with their mental health.

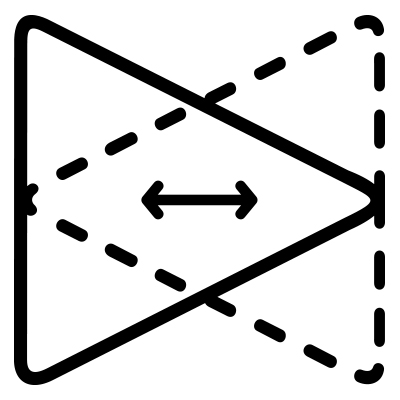

“People have talked about the gut-brain connection for a long time, but usually in the context of people who are depressed or anxious and, as a result, have physical symptoms. But that’s not the whole story,” says Treisman. “We are emphasizing that this is bidirectional. Signals emanating in the gut can influence how the mind feels.”

While Pasricha left Johns Hopkins in 2022 to become chair of medicine at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, the impact that the Amos Food, Body and Mind Center had in its eight years of existence continues to be felt at Johns Hopkins and beyond.

“We have broken new ground, and as both of us and our colleagues continue to see new patients who come in with a devastating array of symptoms, we are now able to get a lot of people better — people who would never have gotten better before,” Treisman says. “It’s remarkable.”